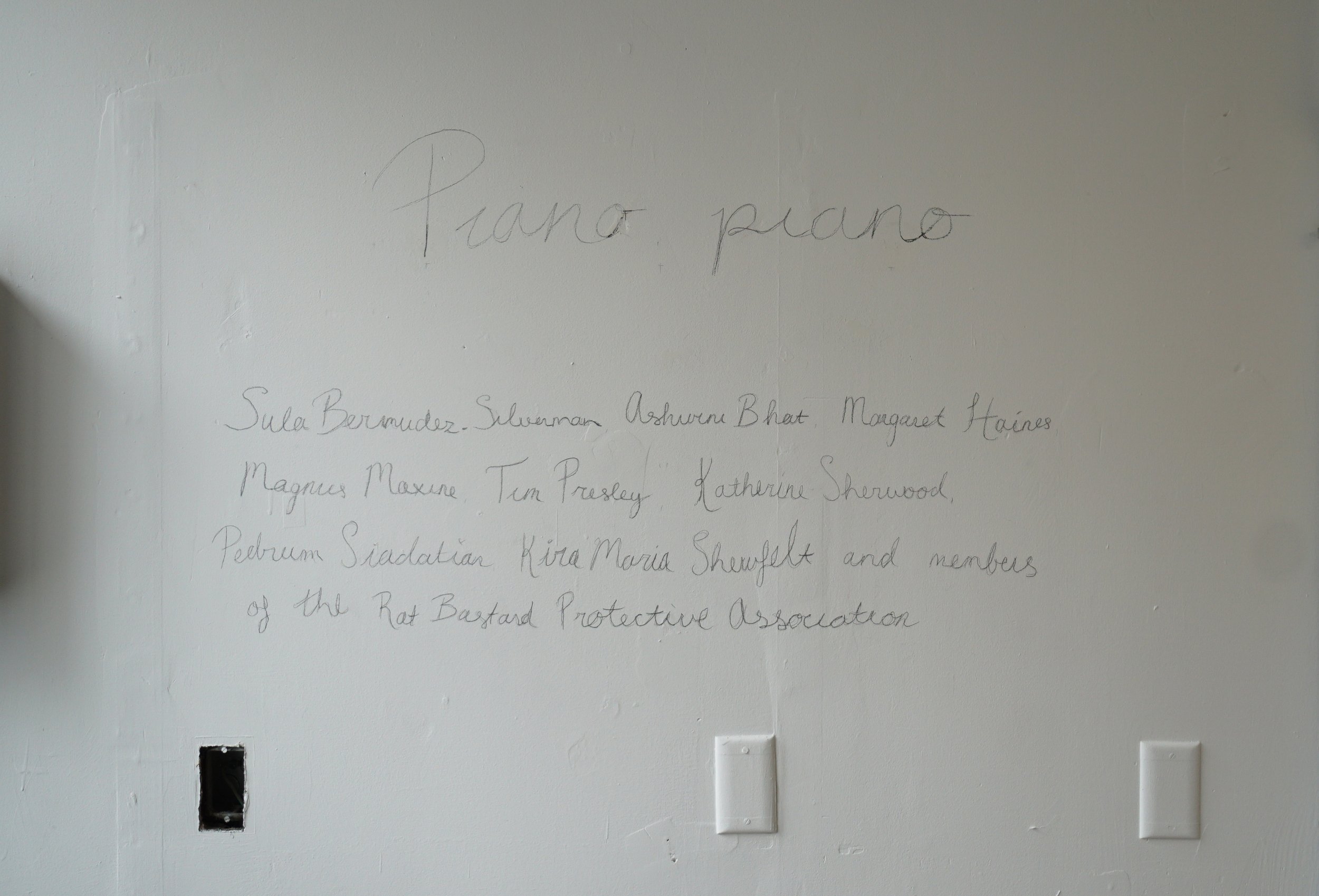

piano, piano

Sula Bermudez, Ashwini Bhat, Margaret Haines, Magnus Maxine, Tim Presley, Katherine Sherwood, Pedrum Siadatian, Kira Maria Shewfelt, and members of the Rat Bastard Protective Association: Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, George Herms.

Curated by Mattea Perrotta & Lara Schoorl

May 13 - June 17, 2023

620 Kearny St.

Et al.

For inquiries, contact aaron@etaletc.com

Sula Bermudez-Silverman, 2021, freshwater cultured pearls, epoxy resin, transparency film, 9 x 8 x 1 inches

“I want to possess the atoms of time” Clarice Lispector writes in the opening page of Água viva, mid monologue on seizing the instant, the now, the present is, and recognizing that it is only in love “the limpid star-like abstraction of feeling” that this moment can be taken hold off, its fleeting delayed, at least experientially. Spinning off the Italian word piano, meaning slowly, and double functioning as title for the exhibition, we attempt to imagine another flow of time than what society runs by. For example, slowed down time, a suspense, natural time, or dream time. How do our minds and bodies experience in these alternate time frames? Heightened and intense thought processes and emotions can run at their own pace, "free" while possibly otherwise "trapped" by a lack of time to sit with them. Memories can appear, realities conflate with fantasies, history with the present, inner dialogues communicate with the universe. We were drawn to think about the myriad of possibilities when thinking outside "regular" time through Lispector's Água Viva, in which words are strung together so frantically, representing exactly how one's mind runs but which rarely is captured, or possible to be captured, in words. Art, including poetry, seems to be able to get closer to non-linearity that way than language.

The works in Piano, piano deal with time and their relationship to it. For each of her paintings Magnus Maxine takes one full newspaper, one curated and archived day. The frontpage of The New York Times, Los Angeles Times or Financial Times become her canvas while the rest of its contents are turned into pulp and used to sculpt a bas relief atop that day’s headline. Each work materially contains exactly one paper, and thus one day. Yet the process of making one work takes up several days. They become an abstract diary, pulped and painted instead of written.

Margaret Haines jumps between vantage points disrupting traditional narratives and clarity of the status quo. She combines references across fields spanning from niche popular culture, astrology and Ancient Greek mythology to early twentieth century philosophy and literature, forming her own esoteric poetics. While often working in film, Haines’s new paintings bring these multitude of sensations into a visually surrealistic environment. A pair of hands have strung a web of chords between its fingers, capturing our gaze then holding it. Metaphysically caught, our vision oscillates back and forth between the strings, tethered to or possibly hypnotized by the illusion of space between them.

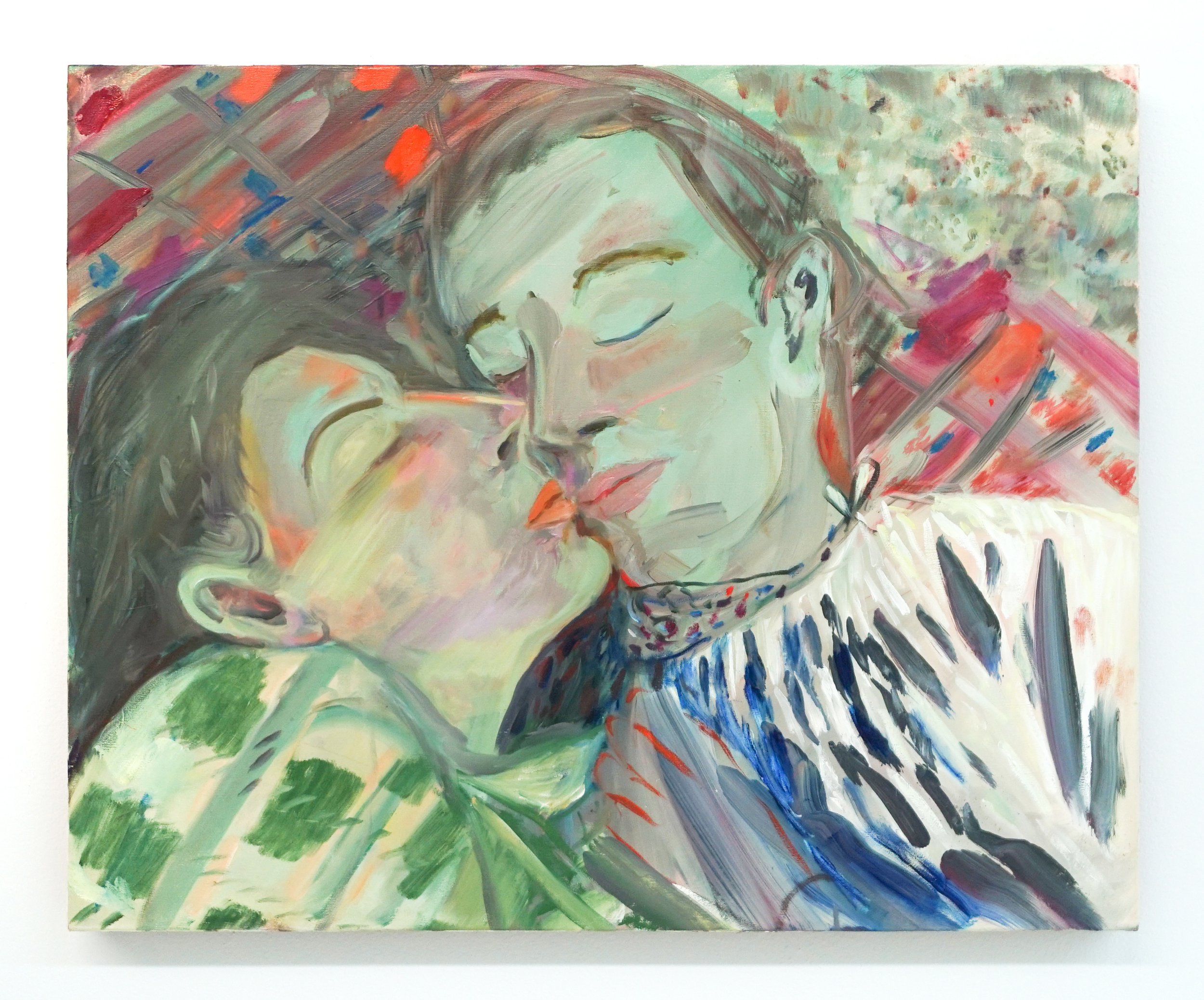

Movement is a play with time, a possible attempt to escape it, be contained by it, follow it. Kira Maria Shewfelt’s paintings share this dynamic play between people, between people and nature and within nature itself. Across both small and large scale she shows us encounters of intimacy in and with the world. The tangibility of her palette captures the fleetingness of movement, which are at times based on memory and at others unfold from imagination. But also the translucency of the various layers of paint, allowing for a dance of multiple dimensions, create a certain openness; a gateway for change for direction as well as emotion, both visible in the butterflies in Daughter, (good morning light, good morning flowers).

As a ceramicist, with a background in dance and literature, Ashwini Bhat cannot escape rhythm; be it of the natural demands of clay, the body, or systems of letters. Sonnet XV (2022-2023), a short, looped film in response to the eponymous poem by Pablo Neruda, is an unexpected crossroads of the various practices that influence Bhat’s work. Neruda’s poem opens with the words “I like for you to be still.” The film then takes off from there; what if I was still. Bhat nods to apparently small personal memory and mundane studio repetitions, yet so evokes larger questions about the ontology of a work, the distinction from its maker and the body as a vessel for creativity. It is a sensual meandering, a visual thought process, grasping at existence beyond (our) time.

As a gateway, a window is both a point of entry as well as a barrier, slippery in nature with two distinct functions. This point of slippage, conceptually and materially, is where Sula Bermudez-Silverman’s work takes off. H-AS OS (2021) is one of her peephole works; windows with translucent frames alternately made from resin or a combination of sugar or salt and resin that visually look similar but over time will become more opaque, depending on their material composition. This pending loss of clarity coincides with a desire to hold on; even the sticky appearance of the resin, in which objects, in this case freshwater cultured pearls shaped like crosses, capture a cast moment. However, holding on not just to pause but also to possibly deconstruct. The windows, suggestive of pasts and futures, urge a questioning of structures already formed that still inform the present.

Almost five decades span between Jesus and Mary (1976) and After Madonna on a Crescent Moon (2023), two works by Katherine Sherwood included in the exhibition. Both portraying Madonna and Child, both emphasizing the heads of each figure. The sculpted bodies in Jesus and Mary, seemingly quickly made and therefore very physically present, have collaged heads surrounded by a red halo. The figures in After Madonna on a Crescent Moon (2023)––based on 15th century painting by an unknown German artist––have masks for faces, made from imagery of scans of the interior of Sherwood’s skull and brain. The pairing of these two works create for an interesting conversation with time. One made in 1976, the year prior to the artist suffering from a cerebral hemorrhage, paralyzing the right side of her body and after which she had to relearn how to paint with her left hand; and the other, made in 2023, the year that seems to mark a post pandemic world. The symbolism and religious imagery intertwined with raw bodily elements push and pull the viewer between mind and body, life and death; it reminds us of the phenomenological allegory of the skull about which Walter Benjamin says: “it gives rise to not only the enigmatic question of the nature of human existence as such, but also of the biographical historicity of the individual. This is the heart of the allegorical way of seeing…”

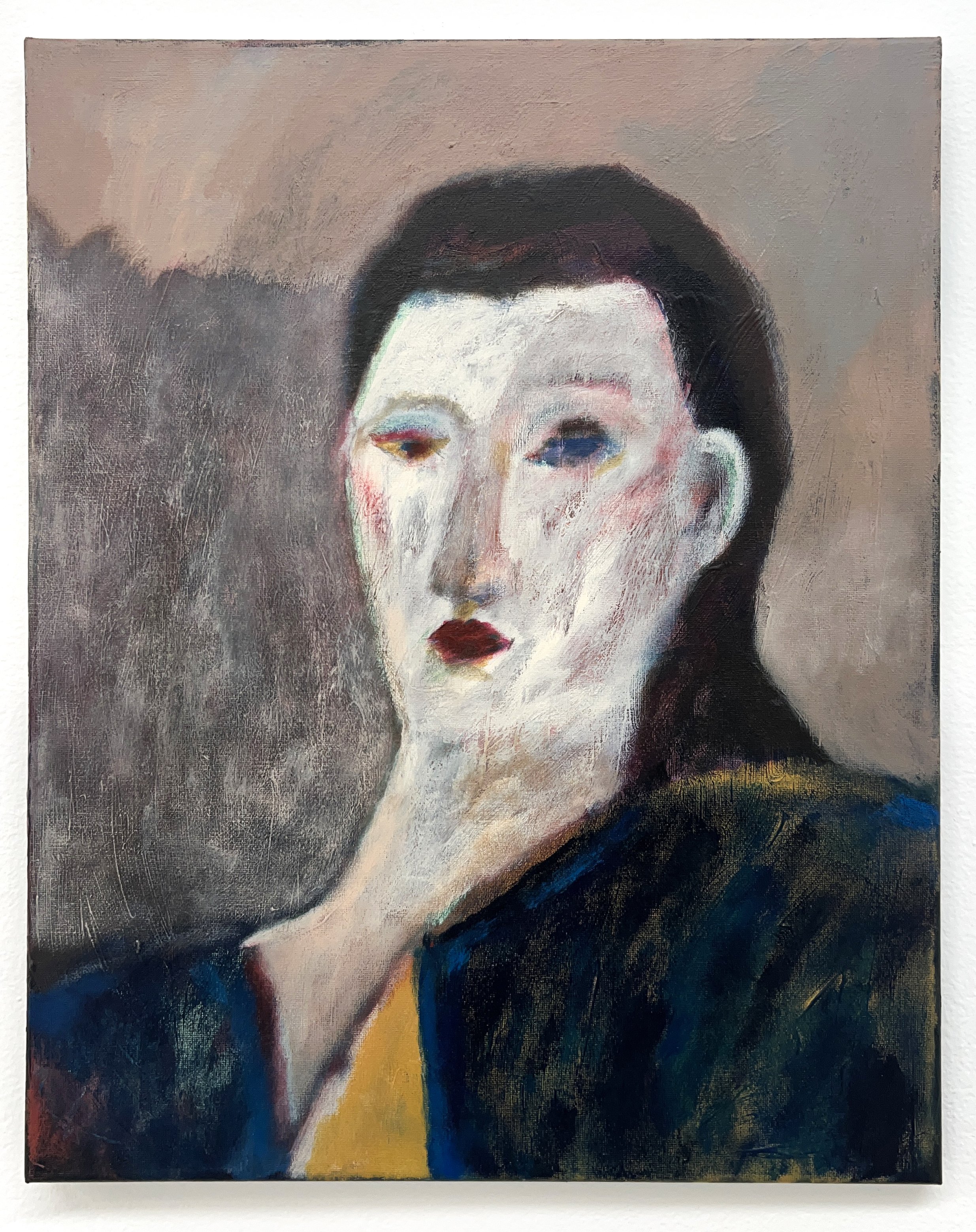

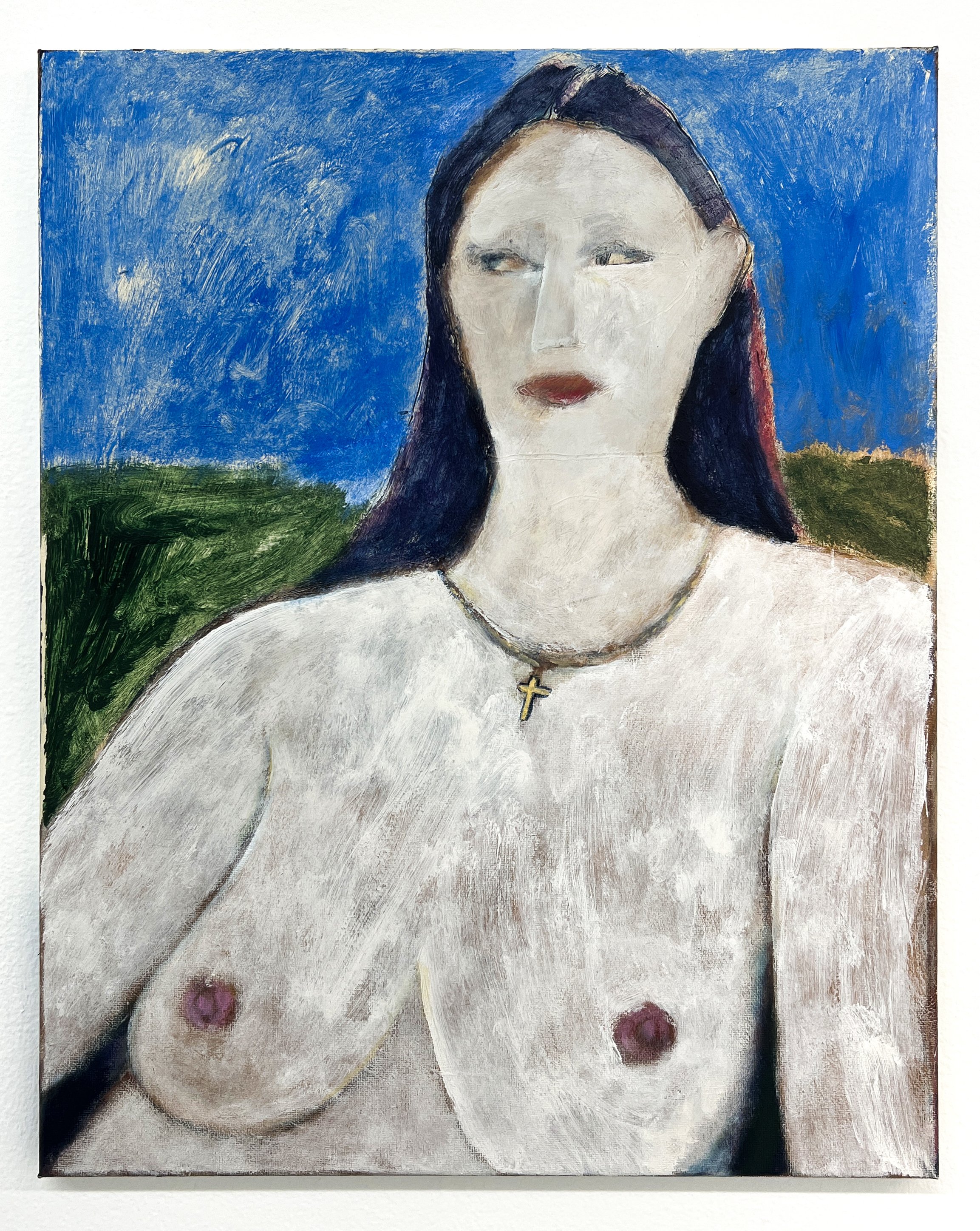

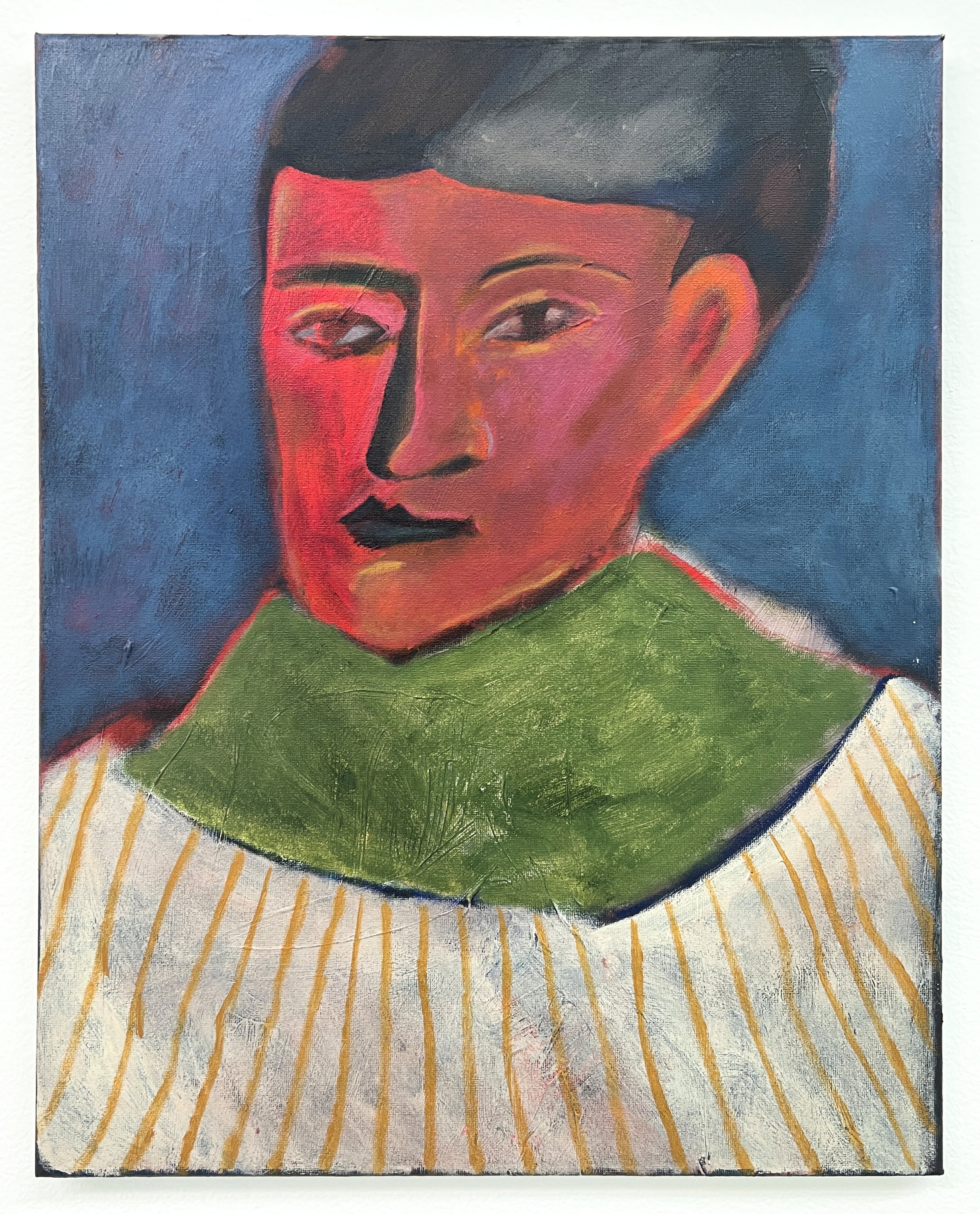

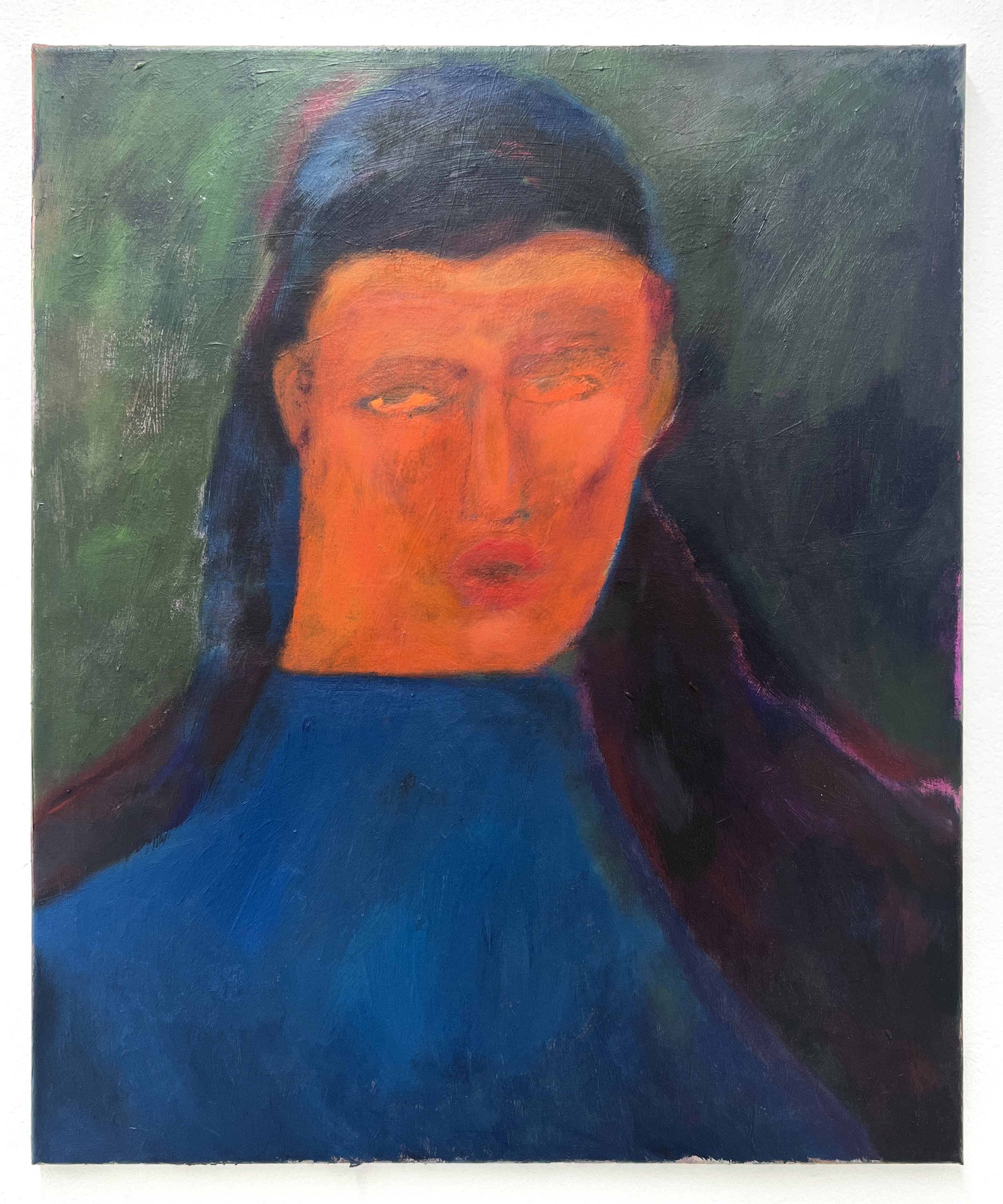

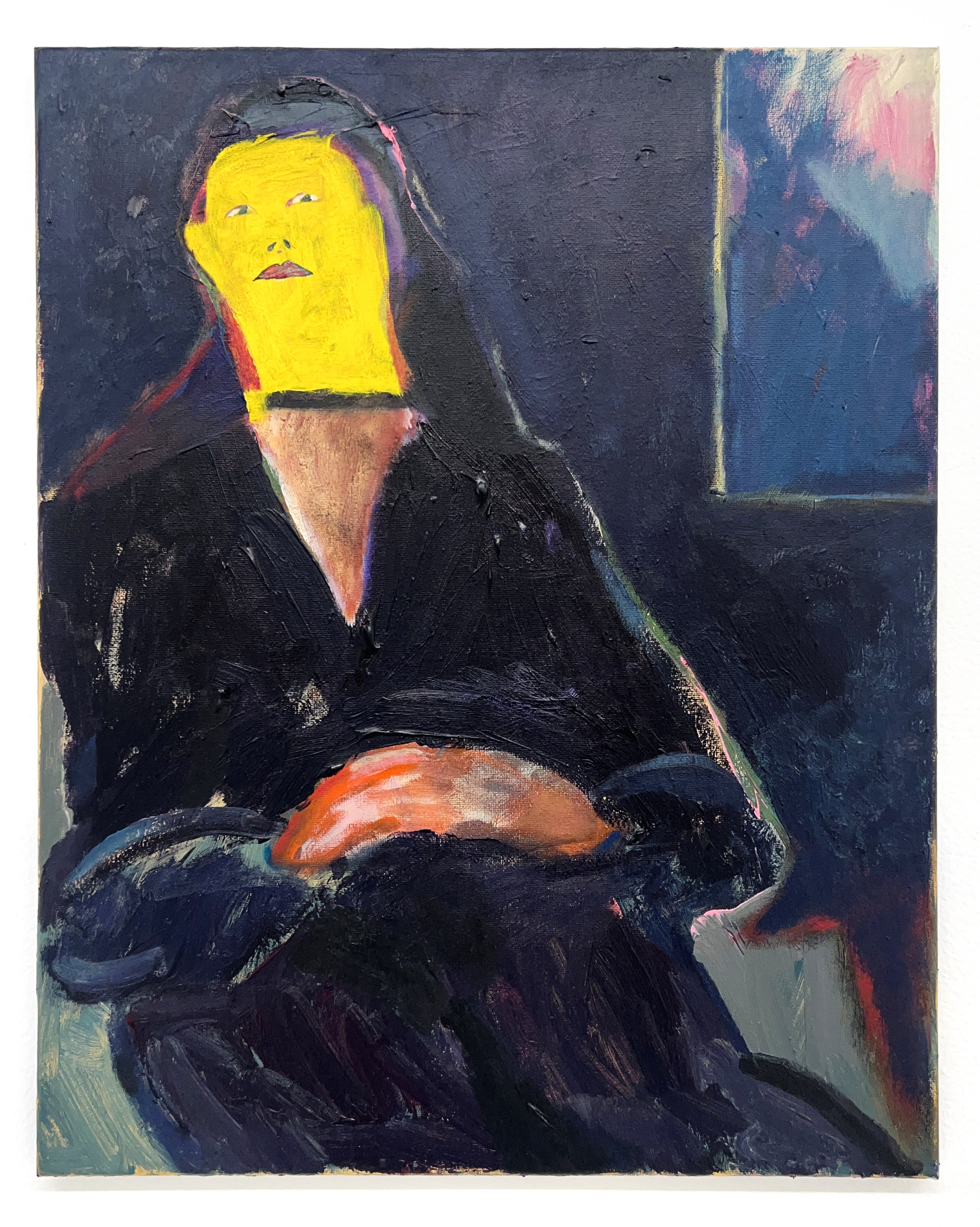

The captured instants rendered in Tim Presley’s portraits are so finite that the figures appear frozen. Yet, an emotive movement is at play. These anonymous people are at the onset of speech, or mid thought; one figure glances at something or someone besides them, another seems to be listening, processing words just uttered to them. However monotone their gazes initially come off as, the unexpected palette and specific directions the eyes follow evoke hints of minute forms of communication. These small moments thus become big, dramatic––windows into imagination; they provide an alternative to being in human time, whether past, present or future. The faces of these others function as mirror or mask, they live in a pause making expression tangible.

Starting with studies on polaroids, Pedrum Siadatian, creates intuitive abstract paintings with his fingers. They are snapshots of expressions, done quickly and childishly, a direct result of his mood at a given moment. The repetition of making a study and then large painting to capture a moment is unfeasible. While it’s complicated to capture any moment, to then go back to that moment and recreate is impossible; the larger works, nostalgic in nature, become romantic gestures through an inevitable collapse of memory and present.

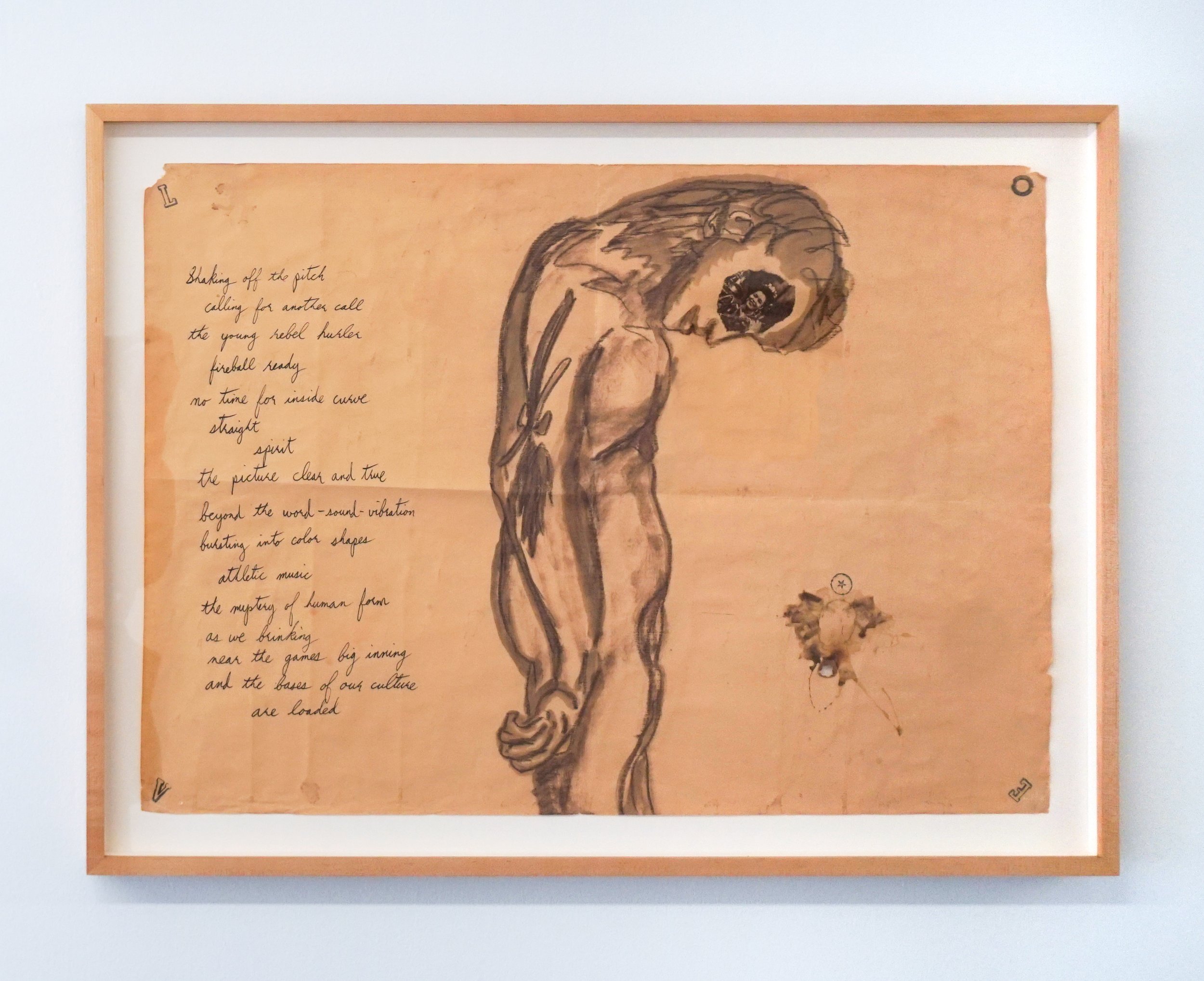

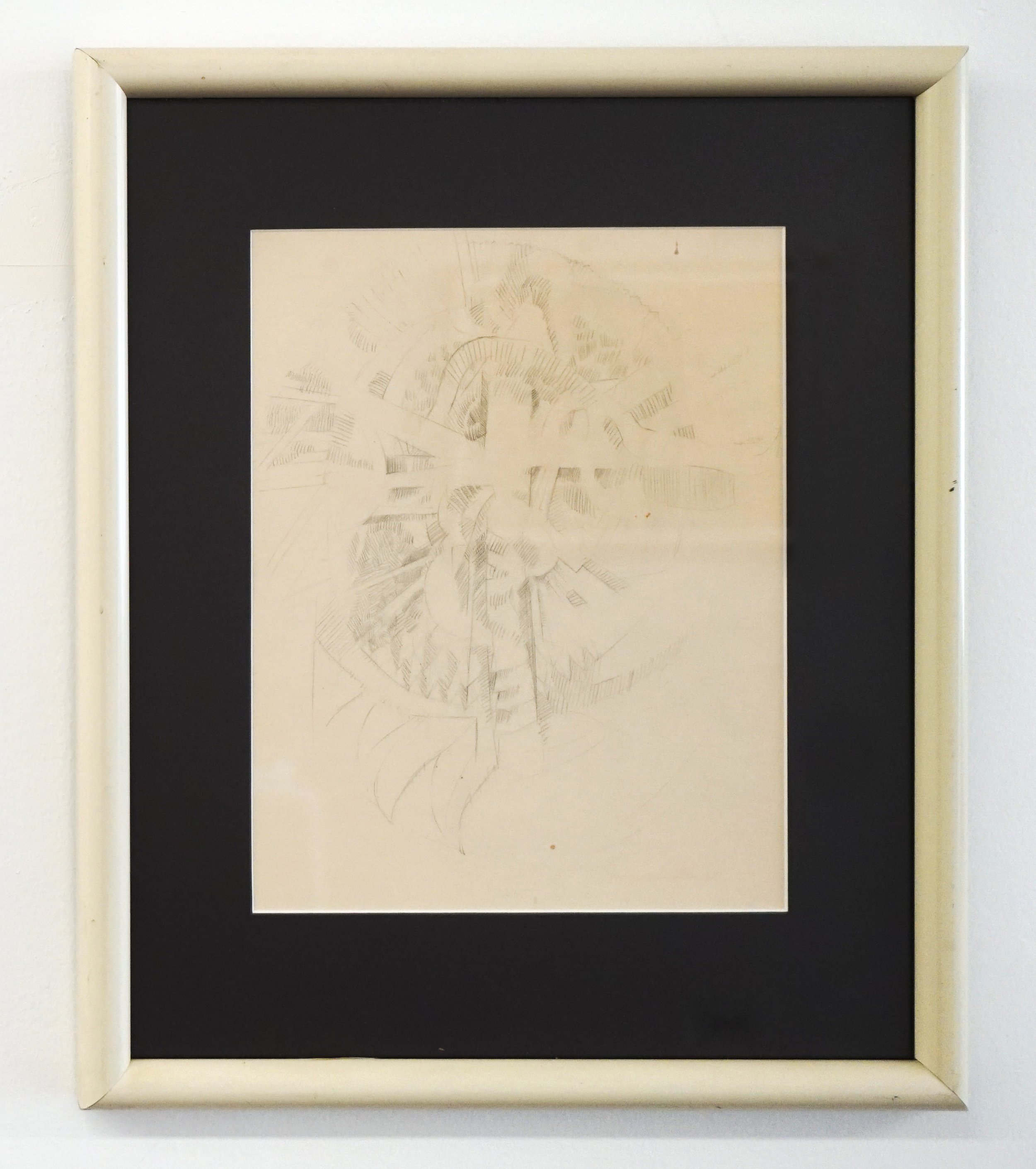

The Rat Bastard Protective Association was a group of artists in the Bay area in the '50s and '60s who lived and worked outside of structures and systems, always making, being in the shadows and in the spotlight. They questioned the institution of (high) art in favor of found objects, trivial moments and materials, and doing things by their own rules. Piano, piano includes three intimate works on paper from the RBPA group by Wallace Berman, Bruce Conner, and George Herms demonstrating a poetic undercurrent of visually and psychologically internal spaces.

—

1. Fitterman, R. and Vanessa Place, Notes on Conceptualisms, Ugly Duckling Press: 2013, p. 26

Wallace Berman, Bruce Connor, George Herms works courtesy of The Landing, Los Angeles.

Ashwini Bhat courtesy of Shoshana Wayne Gallery, Los Angeles.

Magnus Maxine courtesy of Sebastian Gladstone Hollywood, Los Angeles

Katherine Sherwood courtesy of Anglim/Trimble